"Day after day she toiled at the sewing machine uncomplainingly, with a smile for all whenever addressed, and an unkind word was never allowed to pass her cherry-ripe, pouting lips." - Francis S. Smith

Throughout the late 1800s, a literary genre evolved and held the public's interest that was centered around working-class women. Stories were frequently circulated as inexpensive novels, newspaper features, and in theatrical productions. It was a time of increasing employment for women and the public developed an appetite for adventure, romance, and scandal tied to women's changing roles.

In her book Ladies of Labor, author Nan Enstad described a formula of the era:

Imagine the 1880s story: A working-class woman toiling at a factory suddenly finds herself, through a remarkable chain of calamities, without work, home, or family... thus vulnerable, she is pursued by two men: a dastardly villain of the upper class who wishes to compromise her virtue, and a noble hero, usually the factory owner's son, who falls madly in love with her.Naturally the formula sees the heroine through her challenges and she ends up with the good suitor, usually wed, and privileged beyond her dreams.

In 1871, Francis S. Smith released a short story "Bertha, the Sewing Machine Girl" along with it's alternate title, "Death at the Wheel." The story was so popular that it was given treatments as longer literary works and a popular stage production.

The 1871 newspaper ad above enticed audiences:

Portraying most wonderful incidents in the vicissitudes of the working girls of New York... Facts and no fiction, and the public confirm it by the crowds that nightly endorse it... all the original thrilling effects by a powerful company.Sounds awesome, and it surely was for its day, though by modern standards the major shortcoming of this genre was the heroine's unwavering virtue meant she never really evolved. Her virtue was without the nuances of a normal person's weaknesses or inner conflicts, yet it brought great reward: the perfect man, comfort, and riches. Of course, this reflected the expectation of the day in terms of women's behavior, temperament and willing roles in society. We were still fifty years from the female characters of F. Scott Fitzgerald, and the independence and daring of the flappers, for example.

For her part, Bertha was described in the original short story:

A glorious creature she was, of twenty summers, with large, lustrous, azure eyes, straight nose, finely chiseled mouth and chin, and broad, white forehead, around which a wealth of golden curls clustered. She was indeed beautiful, and as good as she was beautiful. Day after day she toiled at the sewing machine uncomplainingly, with a smile for all whenever addressed, and an unkind word was never allowed to pass her cherry-ripe, pouting lips.

I've not found the full text of the original story by Francis S. Smith, but you can read the first few chapters as published in the Brooklyn Eagle in 1871 by clicking here.

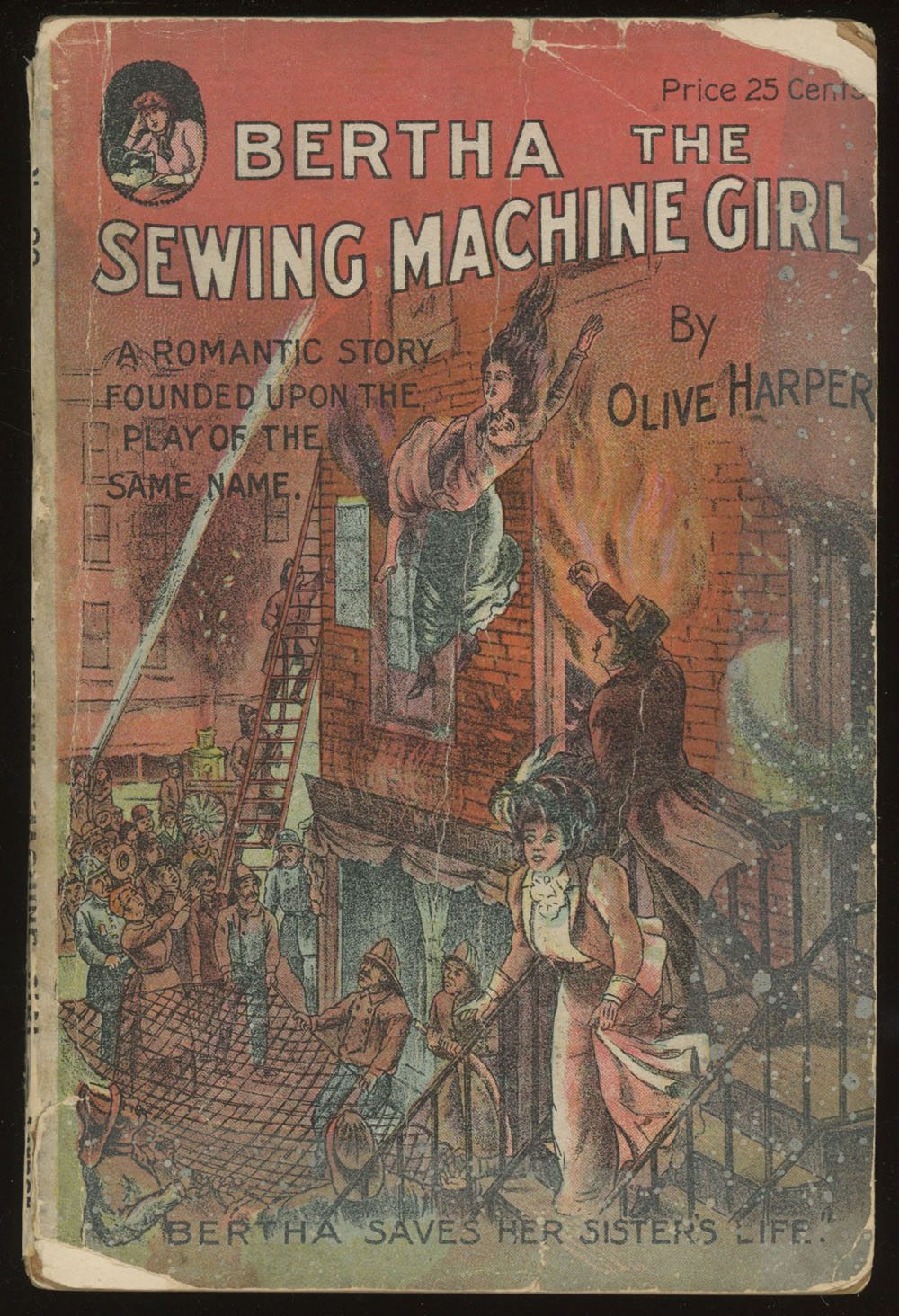

By 1906, the story of Bertha was available in novel form by Olive Harper for 25 cents. No household name today, Harper was indeed well-known and appreciated up to her death in 1915, having written more than 60 books. The cover of Harper's version of Bertha features a scene titled, Bertha Saves Her Sister's Life:

If the harrowing scene on Harper's novel is enough to intrigue you further about the story, you might give a 1933 Jack Benny radio airing a listen. Benny and his radio cast performed the story, but if you're like me, the poor audio quality ultimately overwhelms any merit to the performance.

Of greater interest to me would be the 1926 film version of Bertha, the Sewing Machine Girl, but I've not found it anywhere. Truth be told, if the original story actually had nearly nothing to do with sewing, by the film adaptation it seems the title should have been utterly abandoned, based on a user review at IMDB:

Bertha, the Sewing-Machine Girl is as dated and awkward as its title. This film was made in 1926 but seems more typical of the film fare of 1916. The heroine is a working girl (whom heaven will protect), yet who spends just enough time in a sweatshop to justify the film's title. She quickly gives up her sewing machine for better employment as a switchboard operator, and then even better employment as a lingerie model. Of course, this job makes her prey for men with big black mustaches. - F. Gwynplaine MacIntyreThe point that the 1926 film smacks of 1916 makes perfect sense to me. While it's clear the plot was updated and included what TCM describes as a rescue "in the nick of time in a thrilling motorboat chase," we've already established that the basic premise of the story was quite dated.

|

| Fox Pictures released Bertha in 1926. |

|

| Madge Bellamy played the title role in the 1926 film. |

See what I did there?

|

| Sally Phipps (center) starred as Jessie in Bertha, the Sewing Machine Girl in 1926. |

No comments:

Post a Comment